☝ this keyword

Useful resources:

What is this ?

thisis a binding that is made when a function is invoked, what it references is determined by entirely by the call-site where the function is called. When a function is invoked, an execution context is created which contains the following information:

- Where the function was called from (the call stack)

- How the function was invoked

- What parameters were passed

this

One of the most important properties of execution context is the this reference that will be used for the duration of that function call.

How to determine call-site ?

call-site: The location in code where a function is called (not where it's declared).

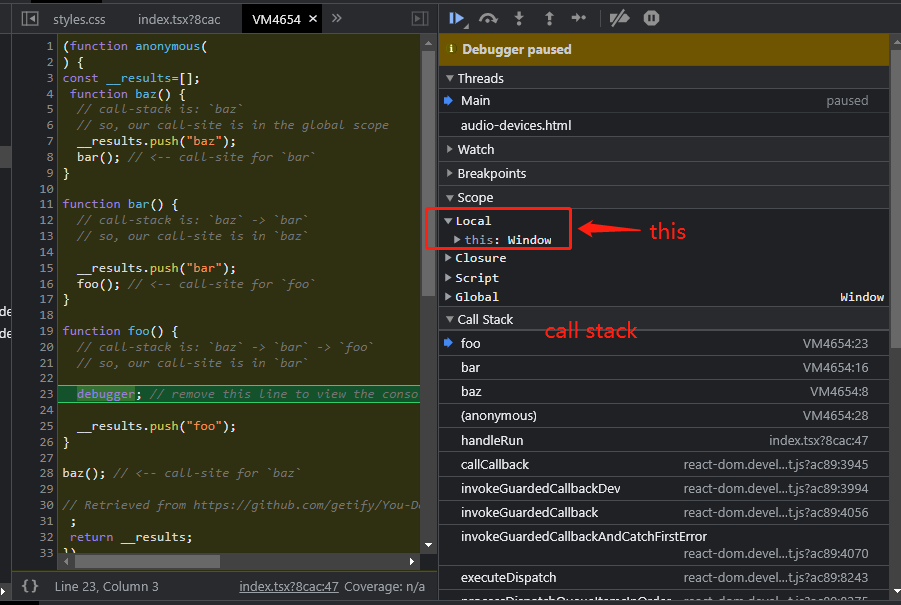

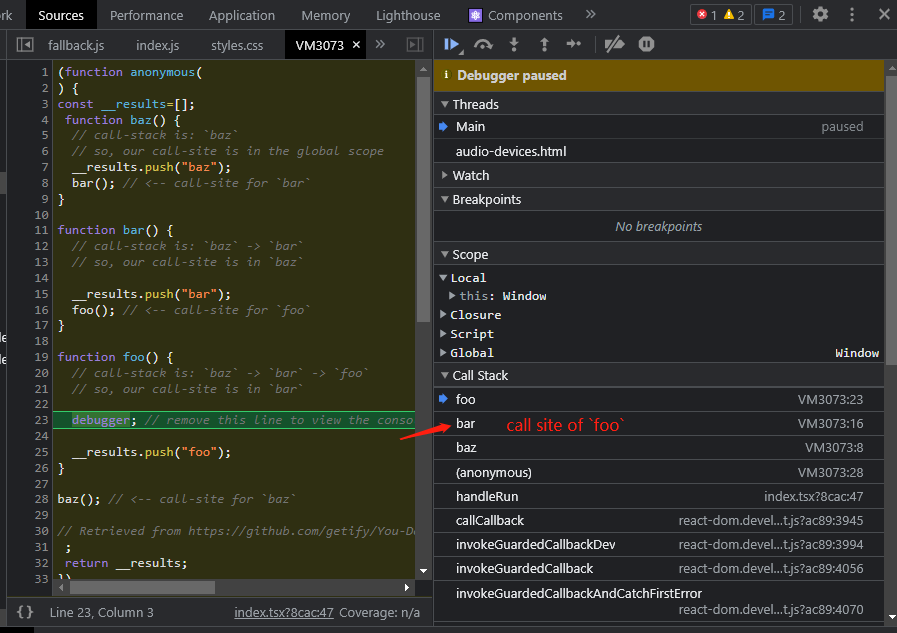

Because call stack is a stack of functions that have been called to get us to the current moment of execution. The call-site of a function is in the invocation before the currently executing function. In other words, it is the second item from the top of call stack. see the the image below

Insert a debugger at the code above

In this example, the call-site of function foo (currently executing function), is in bar.

4 Rules

How to determine where this will point during the execution of a function ?

- Find the call-site

- Determine which of 4 rules applies.

These 4 rules are applied in this order:

- Called with

new? Use the newly constructed object. - Called with

call,apply(orbind)? Use the specified object. - Called with a context object in front of the call? Use that object. e.g.

person.sayName() - Default:

strict mode?undefined:globalThis

Default Binding

If a function is called with a plain, un-decorated function reference, then default binding applies.

The default binding make this points at the global object.

function foo() {

console.log(this.a);

}

var a = 2; // is declared in the global scope

foo(); // 2 -- call-site at this line

Follow the instruction. The first step is to find the call-site

In this example, foo() is called with a plain, un-decorated function reference, so default binding applies.

Strict Mode Behavior

In strict mode, the global object is not eligible for the default binding. That means this will be set to undefined.

function foo() {

"use strict";

console.log(this.a);

}

var a = 2; // is declared in the global scope

foo(); // Uncaught TypeError: Cannot read properties of undefined (reading 'a')

One important detail to remember is that: the global object is only eligible for the default binding if the contents of foo() are not running in strict mode. The strict mode in call-site of foo() is irrelevant.

function foo() {

console.log(this.a);

}

var a = 2; // is declared in the global scope

(() => {

"use strict";

foo(); // 2

})();

Implicit Binding

When a function preceded by an object is called, the implicit binding rule says: that object should be used as the function call's this binding.

Because person is the this for the sayName() call, therefore, this.name is synonymous with person.name.

Only the last object reference matters to the call-site.

Implicitly Lost

One common issue of implicit binding is that it might lose its this binding. That usually means this falls back to the default binding which is either the global object or undefined, depending on strict mode.

function sayAgeFunc() {

console.log(`Hello, I'm ${this.age} years old.`);

}

const person = {

age: 22,

sayAge: sayAgeFunc,

};

var age = "global age!!!";

const sayAgeStandAlone = person.sayAge;

sayAgeStandAlone(); // Hello, I'm global age!!! years old.

In this example, the call-site of sayAgeStandAlone() is a plain, un-decorated call, therefore the default binding applies.

function sayNameFunc() {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${this.Name}.`);

}

function sayAgeFunc() {

console.log(`Hello, I'm ${this.Age} years old!`);

}

function introduce(first, second) {

first();

second();

}

const person = {

Name: "xiaohai",

Age: 22,

sayName: sayNameFunc,

sayAge: sayAgeFunc,

};

var Name = "[[Global Name]]";

var Age = "[[Global Age]]";

person.sayName(); // Hello, my name is xiaohai.

person.sayAge(); // Hello, I'm 22 years old!

introduce(person.sayName, person.sayAge);

// Hello, my name is [[Global Name]].

// Hello, I'm [[Global Age]] years old!

As you can see that, this is changed unexpectedly, we don't have control over how the function will be executed. That means that we have no way of controlling the call-site to make function call's this to stick with the intended binding.

Explicit Binding

func.call(), func.apply(), func.bind()

func.call(), func.apply() takes an object as the first parameter which will be used as this, and invoke the function. Because you are directly defining what you want the this to be, it is known as explicit binding.

function sayNameFunc() {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${this.Name}.`);

}

const person = {

Name: "xiaohai",

sayName: sayNameFunc,

};

person.sayName(); // Hello, my name is xiaohai.

sayNameFunc.call(person); // Hello, my name is xiaohai.

Invoking sayNameFunc with explicit binding by sayNameFunc.call(...) enable us to bind its this to be person.

If a primitive value (string, boolean, or number) is passed as the first parameter this binding, the primitive value is wrapped in its object-form (new String(...), new Boolean(...), or new Number(...), respectively). That behavior is known as "boxing".

Hard Binding

However, func.call(), func.apply() still doesn't solve the problem (implicit lost) "a function losing its intended this binding".

But a variation pattern around explicit binding can solve the problem.

We can use ES5: Function.prototype.bind to achieve the same result shown above. Below is a simple version of bind.

function bind(func, thisObject) {

return function (...args) {

// Don't forget to return the value computed by the func

return func.call(thisObject, ...args);

};

}

func.bind(...) returns a new function that will call the original function with this set as you specified.

In ES6, the function created by bind(...) has a name property that derived from the original target function. newFunc = func.bind(...), newFunc's name property should be bound func

new Binding

When a function is invoked with new in front of it, the following things are done automatically.

- a brand new object is created.

- the newly constructed object's prototype is set to

Func.prototype. see constructor - the newly constructed object is set as the

thisbinding for the function call. - execute the constructor to populate the newly constructed object if necessary.

- if there is no

return, the function will return the newly constructed object. Otherwise, perform the normal return.

mimic new operator

function mynew(Func, ...args) {

// 1.create a brand new object

const obj = {};

// 2.set the new object's prototype to be the Func.prototype.

obj.__proto__ = Func.prototype;

// 3.set `this` using .apply() and run the constructor code

let result = Func.apply(obj, args);

// 4.check if the constructor returns

return result instanceof Object ? result : obj;

}

Priority of Rules

What happened if the call-site has multiple eligible rules? What order to apply these rules?

- new binding

- explicit binding

- implicit binding

- default binding has the lowest priority among the 4.

Explicit vs Implicit

function sayNameFunc() {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${this.Name}.`);

}

const person = {

Name: "xiaohai",

sayName: sayNameFunc,

};

const person2 = {

Name: "dan-dan",

};

person.sayName.call(person2);

// Hello, my name is Hello, my name is dan-dan.

new vs Explicit

Binding Exceptions

If you pass null or undefined as the first argument to call, apply, or bind, the value you passed will be ignored, and instead the default binding rule applies.

function sayNameFunc() {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${this.Name}.`);

}

const person = {

Name: "xiaohai",

sayName: sayNameFunc,

};

var Name = "[[Global Name]]";

person.sayName.call(null);

// Hello, my name is [[Global Name]].

Lexical this

ES6 introduces arrow-function which doesn't follow the rules specified above.

arrow-functions adopt the this binding from the enclosing (function or global) scope.

arrow-function in object literal

const person1 = {

Name: "xiaohai",

sayName: () => {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${this.Name}`);

},

};

const person2 = {};

person2.Name = "xiaohai";

person2.sayName = () => {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${this.Name}`);

};

// pre-es6

var self = this; // captures this

const person3 = {};

person3.Name = "xiaohai";

person3.sayName = function () {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${self.Name}`);

};

function sayName() {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${this.Name}`);

}

var Name = "[[Global Name]]";

person1.sayName(); // Hello, my name is [[Global Name]]

person2.sayName(); // Hello, my name is [[Global Name]]

person3.sayName(); // Hello, my name is [[Global Name]]

sayName(); // Hello, my name is [[Global Name]]

function Person(name) {

this.Name = name;

this.sayName = () => {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${this.Name}`);

};

// pre-es6

var self = this;

this.sayNameFunc = function () {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${self.Name}`);

};

}

const person = new Person("xiaohai");

// polyfill: these two ways of defining functions have the same effect

person.sayName();

person.sayNameFunc();

Instance methods in class are just normal function. see below

Questions

window.name = "hello";

function Foo() {

console.log(JSON.stringify(this)); // {}

this.name = "bar";

this.getName = function () {

return this.name;

};

}

const { log } = console;

let foo = new Foo(); // This line logs the newly constructed object {}

let getName = foo.getName;

log(foo.getName()); // new binding

log(getName()); // implicit binding lost - use default binding

log(Foo.bind(foo).getName); // Foo.getName is undefined

var obj = {

a: 1,

foo: function (b) {

b = b || this.a;

return function (c) {

console.log(this.a);

console.log(b);

console.log(c);

};

},

};

var a = 2;

var obj2 = { a: 3 };

obj.foo(a).call(obj2, 1);

obj.foo.call(obj2)(1);

obj.foo.call(obj2) create a function close over foo so it can access to the value of b defined in foo. Secondly, it is a standalone function invocation, default binding rule is applied to determine whether this should point to globalThis or undefined .